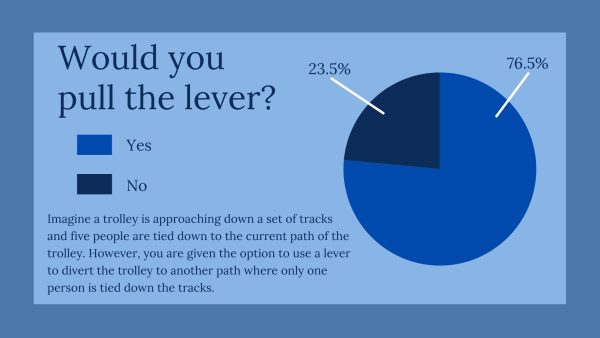

The trolley problem is a moral dilemma that was first introduced in Philippa Foot’s 1967 “The Problem of Abortion and the Double Effect” to explore our take on the morality of abortion and the multiple effects our actions can cause. The dilemma has many variations though the most commonly known is an unstoppable trolley headed towards five people tied down to the tracks, ensuring their deaths. As the witness, you have the choice to pull a lever which diverts the trolley from its path and head towards another track with only one person tied down to the tracks. The question is: will you pull the lever?

Utilitarianism is the idea that actions are moral if they bring the most benefit to the majority, making the choice to pull the lever a moral obligation to minimize harm, only losing one life instead of five.

Leah Enerva ‘27, who chose to pull the lever, said, “No matter how much I would try to save all, I would save the masses at the end of the day and somehow live with blood on my hands.”

Alternatively, deontological ethics focuses morality on what is right and wrong, often not considering the outcomes. One that follows these ethics would not pull the lever because they would be responsible for killing a person.

An anonymous student said, “I would not pull the lever because I could not live with the guilt of intentionally hurting someone, even if it was just one person. I would let the events unfold as they were set to happen; it is not my place to interfere.”

Naomi Wronkiewicz ‘26 said, “First off, [I] would definitely freeze up and be unable to pull the lever. I understand that the inaction will lead to more death, but [I] honestly don’t think [I] could kill someone, especially if [they’d] be unwilling to sacrifice themself.”

Combining the utilitarian and deontological ways of thinking, Sylas Vasquez ‘28 said, “The obvious answer is to pull the lever but there are many things that come into play when in the situation other than five is more than one. As a human being the act of killing someone else weighs on your [conscience] and pulling the lever would be directly killing someone. Other things come into play like what kind of people are the people on the track. I would want to pull the lever yet I wouldn’t be able to bring myself to do it.”

Likewise to deontological ethics, Foot discusses the Double Effect Doctrine which deems bad actions permissible as long as the harm towards the innocent was not intended. When applying this to the problem, the lever would not be pulled because there is an intent to harm the person on the alternative track while there was never intentions to harm the five people on the track.

Foot’s trolley problem later came to have many variations such as the Fat Man Problem, Fat Man Villain Problem and Transplant Trolley Problem.

In the Fat Man Problem, a trolley is headed towards five people tied down on the track and the only way the trolley can be stopped is to push a fat man who has enough mass to stop the trolley but in return, the man must die. A utilitarian could justify pushing the man because more lives would be saved while a deontologist could argue that pushing the man is murder and therefore immoral.

In the Fat Man Villain Problem, the same situation as the Fat Man Problem is used but this time the man is responsible for putting the five people on the tracks. Utilitarianism in this case would justify pushing the man to again, save more lives and also bring justice to the five people tied on the tracks. Deontological ethics states that consequences should match the inflicted harm which is subject to interpretation based on the individual.

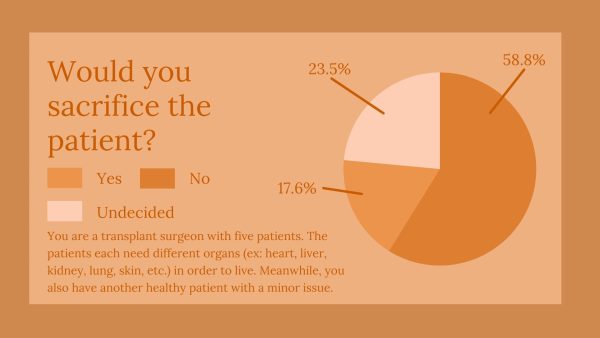

Lastly, in the Transplant Trolley Problem, you are a transplant surgeon with five patients in need of different organs and one patient that has all the needed organs to save the five people. The healthy patient can be killed and have their organs harvested to save the five people or nothing can be done and the five people will die. In the real world, sacrificing the healthy patient would go against medical ethics. However in theory, utilitarianism would sacrifice the healthy patient.

In response to the Transplant Trolley Problem, Jayden Covarrubias ‘27 said, “[I would not sacrifice the patient] because they [shouldn’t] deserve to give up their healthy body.”

Dulce Vega ‘27 said, “The healthy person isn’t required to give their organs.”

I do agree that the healthy patient is not obligated to give up their body to save others because it is a matter of consent. If you believed it was morally correct to kill a person to donate their organs, what is stopping people from killing people for organs now?

Using the different approaches that were stated previously, there are justifications for every choice to each situation but based on the [number] responses from students, the consensus appears to be that it is moral to pull the lever in the original problem and it is moral to push the man in the Fat Man Villain Problem. On the other hand, students were less likely to sacrifice the one to save the five if the minority was someone they loved. They were also more likely to not sacrifice the healthy patient.

I found it really interesting that the majority of us are only willing to sacrifice one person under certain circumstances. For example, in the original trolley problem and the organ donor one, five people are bound to die if nothing happens and in both situations you kill someone to save them.

Some may argue that they are different situations either way, the choice you make determines whether one person or five people die. At the end of the day, it’s up to the individual to pick what is right.